Blog

The Ultimate Guide to Iranian Hospitality: Navigating Taarof and Etiquette in a Persian Home

The Ultimate Guide to Iranian Hospitality: Navigating Taarof and Etiquette in a Persian Home by Voda24

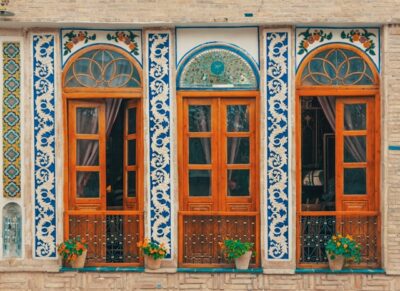

Imagine traveling through a country where you are invited into strangers’ homes for dinner, offered endless cups of tea, and taxi drivers refuse to take your money.1 This isn’t a traveler’s fantasy; it’s a typical experience with Iranian hospitality. Visitors to Iran are consistently overwhelmed by the warmth, generosity, and kindness they receive. People welcome foreigners with open arms, eager to share their culture, food, and time, often treating strangers as friends.2 For many travelers, it is this profound sense of connection that stays in their hearts long after the architectural marvels have faded from memory.3

However, this legendary hospitality is built upon a complex and ancient system of social etiquette that can be bewildering, or even “maddening” 4, to outsiders. It is an unwritten social code, a dance of politeness so nuanced that it can be deeply confusing for those who don’t know the steps.5

At the center of this cultural code is a single, all-important concept: Taarof.

Understanding Taarof is not just a travel tip; it is the key to unlocking Persian culture. It is an “art of communication” 7 and the absolute cornerstone of all social and business etiquette in Iran.8 This guide is designed to serve as your definitive “cornerstone” resource 9, providing a comprehensive, step-by-step journey for any guest in an Iranian home. The primary anxiety for most visitors isn’t safety, but the fear of committing a social faux pas. This guide exists to remove that anxiety.

We will demystify Taarof, exploring not just what it is, but the deep psychology of why it exists. We will then walk you through the chronological journey of a mehmooni (a gathering or party) 10, from the invitation and gift-giving to the dining table and the long goodbye. Finally, we will provide a “cheat sheet” of essential Farsi phrases and a critical list of common faux pas to avoid. Iranians are famously understanding and “unlikely to take offense easily” 11, but your effort to understand their culture will be the most valuable gift you can bring.

The Heart of Persian Politeness: What is Taarof?

Before one can navigate a dinner invitation or a taxi ride, one must first grasp the concept of Taarof. It is a complex system of ritual politeness 12, an “art of communication” 7, and a cornerstone of Persian culture.8 In its simplest form, it is a social dance where what is said often differs—sometimes dramatically—from what is actually meant.12 It is a performance of civility where people say things out of politeness that are not literal.13

First, a practical note on pronunciation. For British or European speakers, it is “ta” (with the ‘a’ pronounced as in ‘far’) followed by “roff”. For North American speakers, it is “tar” (like the black, gooey substance) followed by “off” (as in ‘get off’).8

The Psychology: Why Taarof Exists

On the surface, Taarof is about showing respect, maintaining social harmony, and expressing politeness.8 It is a performance of humility, selflessness, and deference.14 In a hierarchical society, it provides a clear script for interactions, showing “preferential seating to the person who has the higher seniority” 12 or managing relationships between individuals.14

However, this only scratches the surface. To truly understand Taarof, one must look deeper into history. It is a sophisticated, and at times profound, social survival mechanism.

One former Iranian political prisoner described it as “artful pretending,” noting, “You never show your intention or your real identity… you’re making sure you’re not exposing yourself to danger, because throughout our history there has been a lot of danger there”.8

This historical context is key. Iran’s history is one of millennia-long influence and occupation by various powers—Greeks, Arabs, Mongols, Turks—as well as more recent imperialist influences from Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

16 In a social and political environment where direct, transparent communication could be perilous, Taarof evolved. It became a sophisticated social code that allows for “artful pretending” 8, a way to manage relationships, show respect, and protect one’s true intentions without resorting to open conflict or exposing one’s vulnerabilities.

It is a form of cultural ‘soft power.’ It allows a shopkeeper 4 or a taxi driver 14 to maintain their honor and dignity by “playing the role of a good host” 14, even in a commercial transaction. They are not merely a driver; they are a host welcoming a guest to their “kingdom” (their taxi). This ancient heritage of welcoming guests is at the heart of the practice.14

The Scope: Where You Will Encounter It

Taarof is, in a word, “inescapable”.7 It applies to “almost any situation in which there is human interaction, domestic, social, business, wherever, whenever”.8 It is used with strangers, friends, and family, guiding every interaction.7 While the rituals of Taarof may lessen as a relationship becomes closer and more intimate 14, it remains the default setting for all social conduct.

Taarof in the Wild: Common Scenarios & How to Decode Them

For a foreigner, this is where the theory becomes practice. Here are the most common Taarof scenarios and the scripts you need to navigate them.

Scenario 1: The Payment Battle (Taxis, Shops, and Restaurants)

This is the most common and confusing Taarof trap for tourists.5

The Scene: You take a taxi, buy a souvenir, or finish a meal. You ask the driver, shopkeeper, or waiter for the price.

The Taarof Response: They will almost invariably smile and say, “Ghâbel nadâre“.4

The Translation: This literally means, “It is nothing” or “It is not worthy of you”.4 They are implying that you are so important, the item is not worthy of you.4

The Mistake: The confused tourist takes this literally, thanks the driver, and starts to leave.5 One travel blogger recounted this exact scenario, noting that upon his accepting the “free” ride, the driver was suddenly “less enthusiastic”.5

The “Script”: You are expected to play your part.

-

You: “How much is it?”

-

Them: “Ghâbel nadâre.”

-

You (Must Insist): “Khâhesh mikonam” (Please, I insist).17

-

Them (May Taarof again): “Mehman e man bashid” (Be my guest).17

-

You (Insist again): “No, please, I insist. How much do I owe you?”

The Rule: You always pay.4 This is a “fake ta’rof” 8; both parties know it’s a game, a ritual of respect. The only exception would be an “extreme circumstance” where you have, for example, saved the person’s child from a life-threatening illness.4

Scenario 2: The Invitation Dance (The “Rule of Three”)

The Scene: You meet a kind Iranian in a park or a shop. After a short conversation, they invite you to their home for dinner that very night.13 Is this a genuine invitation?

The Taarof Invitation: Often, it is not. This is “the practice of asking strangers or distant relatives to dinner with the assumption that they will reject the invitation since it is ‘merely taarof'”.13 One guide in Iran even had to intercept such an invitation from a local, later explaining to the tourist that the man was “just practicing taarof”.18

The “Script” (The Rule of Three): This is your most important tool. When offered anything—food, tea, or an invitation—the etiquette is to politely decline the first and second offers.8

-

Them: “Please, you must come to our home for dinner tonight!”

-

You (First Refusal): “That is so kind, thank you, but I wouldn’t want to impose”.12

-

Them (Second Offer): “No, no, it’s no imposition at all! We would be honored. Please come.”

-

You (Second Refusal): “You are too kind, but I am sure you are busy. Perhaps another time.”

-

Them (The Third Offer): “I absolutely insist. It is all arranged. We will pick you up at 8 pm.”

The Rule: If the offer is extended for the third time, it is genuine. You can, and at this point should, graciously accept.8

Scenario 3: The Compliment Trap (Gifts & Possessions)

The Scene: You are a guest in an Iranian home. You admire a painting on the wall or your host’s beautiful watch. You say, “What a lovely antique ring!”

The Taarof Response: Your host will immediately insist you take it. “Ghâbel nadâre… It’s yours, please take it!“.4

The Mistake: The “tourist, completely unaware of taarof, hesitantly accepts—leaving the Iranian now forced to hand over their beloved accessory!”.5 This is a very real danger; many Iranians have lost items they valued by compliment-trapped foreigners.4

The Rule: This is an offer you must refuse, politely and repeatedly. Unlike the Rule of Three for invitations, this is a “Rule of Never.” The host is bound by the rules of hospitality to offer; you are bound by the rules of Taarof to refuse.

The Flip Side: When you give your host the gift you brought (which you must), it is polite for you to play the Taarof game. As you present it, you can say it is “nâghâbel” (unworthy), a small, unworthy token.4 This shows you understand and respect the culture.

Scenario 4: The “Door of Hell” (The Battle for Last Place)

The Scene: You and your host, or a group of Iranian friends, arrive at a doorway, an elevator, or the entrance to a room.

The Taarof Response: A “dance of honour” 8 will immediately break out. Your host will gesture grandly and insist you enter first. You are expected to refuse. They will insist again. This can, and does, “continue… for endless minutes”.20

This situation is so common it is jokingly referred to as “the door of hell”.20 Parodies show friends arguing so long about who goes first that they “start sitting on the floor… by nightfall, they are still arguing!”.8

This ritual reveals the link between Taarof and social hierarchy.12 Between strangers, status is “quickly work[ed] out”.8 This polite battle is most common between equals.8 As a foreigner, you are a mehman (guest), which automatically gives you a place of honor.21

The Rule: As the guest, you should Taarof once. Politely refuse and gesture for your host to go first. When they insist a second time (and they will), you should graciously accept and walk through.

Your Strategy: How to “Win” at Taarof (A Summary for Guests)

-

Observe the Rule of Three: For all casual offers (tea, food, invitations), politely decline twice. If the offer is made a third time, it is genuine.17

-

The Exception: For payment 4 and expensive compliments 5, the offer is never genuine. You must insist on paying, and you must refuse the gift.

-

Read Body Language: A key clue to a genuine offer versus Taarof is consistency. One person noted that if their Iranian friend quickly changed the topic after an offer was refused, it was Taarof. But if they “simply said ‘its okay’ or ‘you are busy'” and persisted, the offer was genuine.22

-

Don’t Opt-Out: You may learn the phrase “ta’rof nadaram” (“I don’t do ta’rof“).8 It is advisable to avoid using this. The goal of your visit is cultural connection.2 Using this phrase is like refusing to play the game, which can be seen as cold or abrupt. It is far better to “play the game” badly and show you are trying. Your awkward, good-hearted effort will be seen as a profound sign of respect, and Iranians will be warm and forgiving of your mistakes.11

Your Guest Journey: A Step-by-Step Guide to a Mehmooni (Iranian Party)

You’ve successfully navigated the Taarof of an invitation and accepted. You are now going to a mehmooni (gathering) at a Persian home. Here is your chronological guide.10

Before You Arrive: Gifts and Dress Code

1. The Perfect Host Gift (You MUST Bring One)

This is a non-negotiable rule. Arriving empty-handed is a significant faux pas.23

This involves another Taarof trap. You may ask your host, “Should I bring anything?” The answer will always be a “negative”.10 They will say, “Just bring yourself!” Do not, under any circumstances, “take their word for granted!”.10

A Guest’s Shopping List (What to Bring):

-

Pastries or Sweets: The most common and appreciated gift is a box of shirini (sweets) from a local confectionery.10

-

Flowers: A beautiful bouquet is always welcome.10 White orchids are considered a particularly nice gesture.26

-

Chocolates: A high-quality box of chocolates is a safe bet.10

-

Nuts: A decorative box of assorted nuts like pistachios and almonds is a traditional gift.25

-

Saffron: A small box of high-grade saffron is a classy and deeply “Persian” gift.26

-

A Gift from Your Country: This is a fantastic gesture and will be greatly appreciated.10

What NOT to Bring: Never bring alcohol. It is illegal and a major social taboo.23

2. Dressing for the Occasion (Public vs. Private)

The rules for dress in Iran are famously split between public and private life.

In Public: The Islamic dress code is mandatory. This applies to all public spaces, which include “cars, hotel lobbies and restaurants”.29 For women, this means a headscarf (hijab), a loose-fitting tunic or coat (manteau) that covers your lower waist, and long trousers or a skirt to the ankles.29 For men, this means long trousers (no shorts) and shirts with sleeves (T-shirts are fine, sleeveless shirts are not).29

Inside the Home: Once you step inside a private home, the rules change completely. “Travelers and locals can freely choose their clothing when they’re inside someone’s house”.29 “You have the freedom to dress comfortably”.30 Female guests will almost certainly be invited to remove their headscarves and manteaus.29

Guest Attire: You should “dress up nicely”.10 Avoid “sloppy clothing”.23 While you can relax your dress code, it’s respectful to “avoid wearing revealing clothes”.29 Think “smart casual.” The act of entering the home and removing your hijab is a powerful symbol of trust—you are leaving the “public” sphere and being welcomed into the private, “family” sphere.

The Arrival: Punctuality and First Impressions

Punctuality: Arriving on time is very important.34 Arriving “early may cause embarrassment if the host is not prepared”.34 Arriving a few minutes (15-30) late is perfectly acceptable, especially in a traffic-heavy city like Tehran, but “don’t make your host wait for an hour”.10

Taking Off Your Shoes (The Cardinal Rule):

You must take your shoes off upon entering an Iranian home.10 This is a steadfast rule of sanitation, as “Almost everything outside of the home is always considered dirty”.35

The Slipper System (A Critical Insight):

This is a small detail that shows great cultural awareness. Your host may offer you slippers.10 Pay close attention. Iranians have separate, dedicated slippers that are used only for the bathroom/toilet.10 “It is considered unclean to wear the same slippers in both the house and the bathroom”.10

This is not just about physical dirt; it is a cultural concept of ritual cleanliness. The “outside” is dirty.35 The “home” is clean. The “toilette” 11 is an ritually “unclean” space within the clean home. Therefore, its slippers must “contain” that uncleanliness. Wearing the bathroom slippers out into the living room is a major cultural faux pas as it is seen as spreading this impurity.

Greetings:

-

The standard greeting is “Salaam” (Hello/Peace) or the more formal “Salaam Alaikum” (Peace be upon you).37

-

Always greet the elders in the room first as a sign of respect.23

-

Be cautious with physical contact. Physical contact “is not allowed between men and women who are not related”.21 Men should never initiate a handshake with an Iranian woman; wait for her to extend her hand first.39

-

The safest bet for an opposite-sex greeting is a warm smile, a nod, and placing your right hand over your heart.

-

Among the same sex, handshakes are common. Among close friends and family, be prepared for three alternating cheek kisses.39

During the Visit: Seating, Conversation, and the Feast

Being Seated: You will “expect to be offered the best seat”.10 This is part of the “preferential seating” for guests and elders.12 As the guest, you are the highest-status person in the room. You should Taarof once (politely decline), but after your host insists, accept the seat of honor.

Body Language: Be mindful of your posture. “Don’t stretch your legs… in the presence of elders,” and “don’t put your feet on the table”.36 The underlying rule is to never show the soles of your feet to another person, as this is considered deeply disrespectful in many Middle Eastern and Asian cultures.

Conversation:

-

Safe Topics: Talk about your family (a much-valued topic 34), your travels in Iran, and your home country. Ask about Persian poetry (Rumi, Hafez 43), art, and history. And, of course, praise the Iranian food.44 Be prepared for personal questions: “Where are you from?”, “How old are you?”, “Are you married?”.46 These are not considered rude; they are a sign of genuine interest in you.

-

Topics to Avoid: Do not bring up sensitive domestic politics or criticize the government.47 Avoid discussions of religion (unless the host leads), and absolutely avoid any discussion of sex or relationships.49 It is also considered poor form for a guest to “complain too much about their personal problems”.34

The Feast (Sofreh):

The heart of the mehmooni is the food. Your host’s goal is to show love and honor through an “abundance of food”.10 Expect to see “more food than guests can eat”.11 You may sit at a dining table, or in a more traditional home, on the floor around a sofreh (a beautifully decorated tablecloth).10

The Taarof of Food (The Second Battle):

This is the second Taarof ritual you must master.

-

Host’s Role: Your host will offer you a second and third helping. They will insist, “Please, take more!”.3

-

Guest’s Role: “The host will assume your initial refusal as Taarof!”.11 A guest is “obliged to refuse it”…14 but only once.

-

The Rule: You must participate. Unlike the “compliment trap” (where you must never accept), you must eventually accept the second and third helpings of food. To genuinely and firmly refuse food is a major faux pas.23 It will be interpreted as “I did not like this food,” which is a deep insult to the host who has “gone to so much trouble”.33

-

Praise the food! This is non-negotiable. “Compliment the food profusely”.23 Use the Farsi phrases you’ll learn below, especially “Daste shoma dard nakone” (May your hand not hurt) and “Kheili zahmat keshidin!” (You’ve gone to so much trouble!).33

Helping Out:

You might be tempted to help clear the table or wash dishes. In Iran, “it’s best not to help washing the dishes… as it may be an embarrassment for your host”.10 You can (and should) politely offer once 10, but respect their decline. This is one “no” that is almost always genuine.

The Art of Leaving: The “Long Goodbye”

In Iran, leaving is not a quick event; it is a process. The “long goodbye” is famous. Expect that “when… saying goodbye on the doorstep the whole process repeats itself and whole new conversations… are enjoyed well into the night”.53

The “Script”:

-

You (Announce Your Intention): You must politely signal your intent to leave by saying, “Ba ejaazeh maa mirim” (“With your permission, we’re going”).54

-

Them (The Final Taarof): Your host will immediately protest. “Bemoon digeh!” (“Stay already!”).54 They may even “offer you to stay overnight”.10 This is a common Taarof; it is best to politely decline.10

-

You (Insist Gently): You must reiterate your need to leave, while expressing profound gratitude for the evening.

-

The Exit: This process can take 20-30 minutes. Your host will “walk… you to the door, to the street, or even to the end of the block, making sure you are safe”.3

Farewell Phrases: The most common farewell is “Khodâ hâfez” (Goodbye, literally “May God protect you”).37 You can also say the warmer “Be omîde dîdâr” (Hoping to see you again) 39, or if it’s late, “Shab bekheir” (Good night).39

A Guest’s “Cheat Sheet”: Essential Farsi Phrases

Learning a few key phrases goes beyond politeness; it shows deep respect. Using the “Advanced Taarof” phrases will astonished and delight your hosts.

| Category | English Phrase | Persian (Farsi) Transliteration | Pronunciation | Context & Cultural Value |

| Greetings | Hello / Peace | Salaam | sa-LAAM |

The universal, all-purpose greeting. Use it with everyone.37 |

| Good morning | Sobh bekheir | sobh be-KHEYR |

Use before noon.38 |

|

| Good evening/night | Shab bekheir | shab be-KHEYR |

Use after sunset. Works as “good evening” or “good night”.39 |

|

| Politeness | Thank You | Mamnoon or Mersi | mam-NOON / mer-SEE |

General thanks. Mersi is a casual French loanword and very common.37 |

| Thank you (very much) | Kheili Mamnoon | KHEY-lee mam-NOON |

For extra emphasis. You will often hear Iranians combine them: “Mersi, kheili mamnoon!“.37 |

|

| You’re Welcome | Khâhesh mikonam | kha-HESH mee-ko-nam |

Standard reply to “thank you”.60 |

|

| Excuse Me / Sorry | Bebakhshid | be-bakh-SHEED |

Use to get attention, apologize, or preface a request.37 |

|

| Please | Lotfan | lot-FAN |

Use when making a request.57 |

|

| Advanced Politeness | ||||

| “Don’t be tired” | Khasteh nabâshid | khas-TEH na-baa-sheed |

Advanced Taarof. A beautiful phrase with no English equivalent. Use it to greet or thank someone who is working (a shopkeeper, your host after cooking). It means, “May you not be tired,” and recognizes their labor.61 |

|

| “Your sacrifice” | Ghorbāne shomā | ghor-BAA-ne sho-MAA |

Advanced Taarof. A very polite, formal way to say thank you or show deference. It literally means “I am your sacrifice”.58 |

|

| At the Table | Bon Appétit! | Nooshe jân! | NOO-she jân |

Said by the host to guests, or by guests to each other. It means “May it be sweet to your soul”.40 |

| It’s Delicious! | Khosh mazeh ast! | khosh-ma-ZEH ast |

Critical! Use this liberally about the food.57 |

|

| “May your hand not hurt” | Daste shoma dard nakone | DAS-te sho-MA dard na-KO-ne |

Critical! The best way to thank a host for a meal, gift, or any effort. It poetically wishes their hands, which prepared the meal, will not hurt.57 |

|

| “So much effort!” | Kheili zahmat keshidin! | KHEY-lee ZAH-mat ke-shee-deen |

Critical! “You’ve gone to so much trouble!” Use this to show profound appreciation for the meal. Your host will love it.33 |

|

| Taarof & Gifts | It’s not worthy (of you) | Ghâbel nadâre | ghaa-BEL na-daa-re |

Host’s Phrase. What a host/shopkeeper says. You must not accept.4 |

| Please, I insist | Khâhesh mikonam | kha-HESH mee-ko-nam |

Guest’s Phrase. Your response to Ghâbel nadâre to insist on paying or politely refuse a gift.61 |

|

| Unworthy (gift) | Nâghâbel | naa-ghaa-BEL |

Guest’s Phrase. What you can say when giving your gift to be polite. “It’s just a small, nâghâbel thing”.4 |

|

| Leaving | With your permission | Ba ejaazeh | baa e-jaa-ZEH |

The polite way to begin the process of leaving.54 |

| Goodbye | Khodâ hâfez | kho-DAA haa-fez |

Standard, polite goodbye. “May God protect you”.37 |

|

| Hoping to see you | Be omîde dîdâr | be o-MEE-de dee-DAAR |

A warm, friendly farewell. “In hopes of seeing you [again]”.39 |

Cultural Faux Pas: 10 Common Mistakes to Avoid in an Iranian Home

While Iranians are incredibly forgiving hosts, you can show your respect by avoiding these common mistakes.

-

Walking in with Your Shoes On. The cardinal sin. Always take them off at the door.23

-

Misusing the Slipper System. Never wear the bathroom-specific slippers 11 out into the main living areas of the house. 10

-

Blowing Your Nose in Public. Blowing your nose at the dinner table or in a group is considered uncouth. If you must, excuse yourself and do it in private.35

-

Taking Taarof Literally. This is the meta-mistake that includes: accepting a “free” taxi ride 5, accepting a valuable item you complimented 4, and believing your host when they say “don’t bring a gift”.10

-

Arriving Empty-Handed. A guest who arrives without a gift (even a small one) may be seen as disrespectful or ungracious.23

-

Showing the Soles of Your Feet. When sitting on the floor or a couch, do not point the bottoms of your feet at anyone. It is considered very rude.36

-

Refusing Food (Too Strongly). Your first refusal will be seen as Taarof. A final, firm refusal of food will be taken as an insult to the host’s cooking.11

-

“Exploring” the House. Your host’s home is their private space. Do not enter other rooms, open closets, or touch personal belongings without explicit permission.34

Conclusion: The Warmth Behind the Rules

The etiquette of an Iranian home can seem complex, a web of unwritten rules and polite fictions. It may be tempting to feel intimidated. But this brings us full circle, back to the heart of Persian culture.

Hospitality is a “cornerstone” of Iranian life.43 It is partly rooted in a religious duty to God—where the guest is seen as a gift and hospitality is a duty.1 It is also, in the modern day, a deeply personal and patriotic desire for Iranians to show foreigners the real Iran, a culture of warmth and sophistication that is often “so often portrayed [negatively] in the media”.1

The complexity of the rules and the depth of the hospitality are not two separate things; they are the same thing. You cannot have this level of profound, honor-based generosity without an equally profound and complex set of rules to govern it. The rules are the vehicle for the hospitality, not a barrier to it.

You are not expected to be perfect. As a solo traveler, you will find people are even more protective, ensuring you “are taken care of”.64 Iranians “understand that visitors may not be fully versed in their local etiquette… They’re unlikely to take offense easily”.11

Your greatest asset is not a perfect pronunciation of Khodâ hâfez. It is your smile, your good intentions, and your willingness to try. Your genuine effort to “play the game,” however awkwardly, will be seen as the highest form of respect. It is this effort that will unlock the door to the most rewarding travel experience of your life, an experience of warmth and human connection that is the true, beating heart of Persian hospitality.